The Lincolns: Portrait Of A Marriage

The Lincolns: Portrait Of A Marriage The Lincolns: Portrait Of A Marriage

The Lincolns: Portrait Of A MarriageAbraham Lincoln loved his wife Mary Todd, but historians have not always treated the latter with much sympathy. She is often portrayed as grasping, materialistic, overly ambitious, contentious, shrewish, temperamental, tantrum throwing, cantankerous, and worse. In her later years, her descent into what is today called manic-depression is well documented, most recently in Jason Emerson’s fine work, The Madness Of Mary Todd Lincoln. But what of Lincoln in this marriage? That has, heretofore, been given relatively short shrift. Daniel Mark Epstein’s book redresses that in admirable fashion.

There is much in the book that will be a familiar to Lincoln readers, but much that is new too, thanks to Epstein’s diligent research. Rumors and myths are validated or dispelled in this sparking narrative by the talented biographer and poet Epstein, and the Lincoln marital relationship is given new life. The author turns a sharp analytical eye on the events that shaped the Lincoln marriage, especially the Springfield years that comprised the first 16 years of their 22 year union and the result is a captivating read even for those who think they already know the entire story.

We come away with a new sympathy for Mary Todd as we learn of the difficulty of raising rambunctious boys — who had been spoiled resolutely by their devoted parents — while Lincoln was riding the Court Circuit and gone for 6 months out of the year. Dealing with a husband that often dropped into a melancholia from which he was not easily aroused could not have been easy for her either. On the other side, Lincoln had his own struggles in dealing with Mary’s hair trigger temper and her reaction to his emotional disengagement. A visit to the apothecary to obtain a gelatin plaster for a nose injury suffered from a firewood wielding Mary Todd is revealing of a frequently fractious relationship. And then on to the White House, where she had to deal with sniping politicians wives who resented her position and where she felt isolated as a daughter of the South with suspect loyalties. Coupled with her husbands’ preoccupation with the war, his growing detachment from Mary, and the death of their beloved Willie, it is no small wonder that this marriage was strained to the breaking point. But there is much love and devotion here too, and Epstein shows it. There is strong evidence this marriage had passed through a firestorm and was emerging with a strengthened bond and a bright promise that was cut short by the ball from Booth’s derringer. Epsteins’ gifts as a researcher and superb storyteller with a lyrical voice are on full display here in a work that is very fulfilling and highly recommended.

Published by Ballantine Books, paperback, January 2009; 539 pages; listed at $16.00; discounted to $10.88 on Amazon.

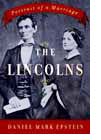

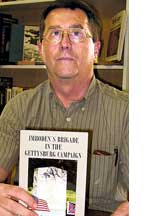

Imboden’s Brigade During the Gettysburg Campaign

Imboden’s Brigade During the Gettysburg Campaign

So much has been written about The Gettysburg Campaign, it is very refreshing to read an aspect of it that has much neglected by historians. Imboden’s Brigade During the Gettysburg Campaign by Steve French is such a book and it fills many knowledge gaps for the Gettysburg reader.

Mr. French is a history teacher who spent 14 years researching Imboden’s role during this campaign, going over newspaper accounts, diaries, memoirs and traveling the roads that Imboden’s men traversed as they went from Virginia into Pennsylvania, and the result is an exciting and comprehensive study that is the 1st of its kind.

In detail, he describes the initial orders from General Lee for Imboden to destroy bridges and rail tracks along the B&O Railroad and then to advance into Maryland and Pennsylvania to secure supplies. Relieving Pickett’s Division , (an answer to a question on the guide exam!), Imboden’s Brigade guarded the supply wagons at Chambersburg.

The most significant contribution to the campaign however, was the order by General Lee to guard the train of wounded Confederate soldiers in the retreat. And this is the part of the book I found most fascinating. From his research, Mr. French’s intimate knowledge of the retreat route is presented to the reader so that one can easily follow it with his own maps of the campaign. Prevented from crossing the Potomac River due to high waters, Imboden organized a defense using wagoners and walking wounded, throwing back an attack by Union cavalry and artillery.

This book is a very welcome addition to the library we all have on Gettysburg. It should be read and digested in the same way as two other worthy and notable books on the retreat: Retreat from Gettysburg by Kent Brown, and One Continuous Fight by Michael Nugent, David Petruzzi, and Eric Wittenberg.

As this book is self-published, there are some minor errors which would have been picked up by a major publishing firm. But certainly, they do not detract from the value of this research and the advancement in knowledge this book brings to our study of Gettysburg!

This book is available from Mr. French, for $23.00, at 8604 Martinsberg Road, Hedgesville, WV 25427.

For another review of this book, please see Book Chat in the March/April 2009 edition of this newsletter. – Ed.

Reveille In Washington 1860-1865

Reveille In Washington 1860-1865Those interested in Washington at the time of the Civil War really have two choices for an in-depth perspective. The most recent is Ernest B. Furgurson’s “Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War”, published in 2004, and the other is Margaret Leech’s classic “Reveille In Washington 1860-1865”. Ms. Leech’s book is considered the standard work on this topic, a winner of the 1942 Pulitzer Prize in History, and it is a comprehensive and scholarly treatment of Washington during the war. It was reissued in paperback in 2001, but does it stand up as a classic of CW literature?

There is much to like about this book. Leech is an excellent writer with a strong narrative voice that keeps the story moving and the reader engaged. Being the scholar that she was, she fills her book with a depth of detail and a keen understanding of the events and the personalities. She has a firm grasp of the military and the political issues, and moves confidently through this turbulent period with muscular descriptions of the significant events and the major players in the drama. For example, of Secretary Of War Edwin Stanton, she writes: “His figure, with its round body and short legs, looked like that of a powerful gnome. He had a dark, mottled complexion; and a tendency to asthma intensified the irascibility of his face. His naked upper lip lay exposed in a thick, rubbery cupid’s bow above the profuse chin whiskers, which seemed to have been tied, like a false beard, to his large ears.” That is an indelible word picture, and the book is filled with them. President Buchanan sets the tone as he is described as “either crying or praying most of the time”, a feckless leader in a state of near paralysis of will. Advised by Massachusetts Congressman Ben Butler to have the independence declaring South Carolina commissioners arrested and tried for treason before the Supreme Court, the judgment of which would determine the rights of secession, Buchanan, “blanching at the very mention of such bold action, could only reply that it would lead to great agitation”. Leech continues, “In ordinary times, he might have retired with honor at the end of his term, but he had been caught in the glare of a crucial moment of history, and even his Southern friends, to whom he had conceded so much, had turned against him.” The old Pennsylvania politico could not vacate the White House fast enough.

Leech’s vivid portrayals will long linger in memory. The frontier aspects of Washington, dirt thoroughfares with pigs and goats running about; the polluted Washington canal; the soldiers coming back, both the dead and the severely wounded, to the 6th street wharf in overwhelming numbers as a result of Grant’s first foray against Lee in the wilderness; the coffin makers working overtime; Mary Todd’s episodes with the Spiritualists; the pillaging done in the White House at the 2nd inaugural public reception on March 4, 1865 where swaths were cut from the drapes in the East and Green rooms by souvenir seeking guests; Clara Barton’s winning over rough teamsters at Fredericksburg by treating them as if they were the finest gentlemen.. And always there is Washington, the bustling, chaotic metropolis in which existed 450 brothels with names like “The Haystack” and “Madam Russell’s Bake Oven”, and where upwards of 5,000 prostitutes worked their trade from the low street toughs to the highest ranks of the political and military establishment; and where the beguiling spy Rose Greenhow plied secrets out of Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson before 1st Bull Run. Leech can be counted on for telling anecdotes but not necessarily humorous ones. She’ll grab you with the good quote such as that of the London Daily Telegraph correspondent’s description of Washington as a “hydrocephalous hamlet, a great, scrambling slack baked embryo of a city basking in the December sun like an alligator on the mud bank of a bayou in July”. Early’s raid toward Washington is given a good treatment, but for the most part battles are mere backdrop. For example, Gettysburg is given one brief paragraph. But as a description of an awakening of Washington from peace to the realities of war in the alarms and panics of enemy threats, both real and supposed, it is a riveting story richly told with a full complement of characters and a plot full of crises, unexpected twists, comedy, bathos, pathos, tragedy and triumph. The downside, for some readers, is that Leech is often prone to fulsome and florid prose that often proves distracting and bothersome at points in the book, and one is compelled at times to wish the work had been more ruthlessly edited. If there is a fancy dress worn by any notable woman at some soiree, you can count on Leech to describe it down to the last brooch. That is both a quibble and a caveat. But to address the question posed at the outset, the answer is that Leech’s work still stands the test of time as a classic and deserves a place in your personal library.

Published by Simon Publications; July 2001; paperback; 524 pages; $39.95, but a Like New used copy can be had for under $15.00 at Amazon.

What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War

What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War I enjoy reading history related books that delve into subject matter about which the casual history reader would probably not be interested. This book is a classic example.

Was the war fought over state’s rights? Or to preserve the Union? Or perhaps to save or eliminate slavery? Those in the public eye and others had very specific ideas as to why the Civil War was fought. Some were lofty and idealistic; some were strictly personal or for profit.

But what did the common soldier think? That young man who farmed his land one day and was learning drill routines the next. What were his thoughts about why he left his home and family, tramped sometimes hundreds of miles, to places heretofore unknown, and suddenly be pointing a musket at a fellow countryman whom he was told was his enemy?

I enjoyed every aspect of this book. It gives great insight to what the common foot soldier was thinking about when he volunteered to fight this war, regardless of what side he was on.

I would rate it an excellent book and found it hard to put down. Ms. Manning does an outstanding job of stating her case right down the middle. She gives equal attention to Northern and Southern viewpoints. Considering Ms Manning has a Ph.D and this is her first book, I was prepared for a tough read but was pleasantly surprised to find the opposite to be the case. Ms. Manning gets into the head of the common soldier, both North and South alike, through their diaries, letters, and camp newspapers and gives the reader a sense of why they were fighting this war. “The fact that slavery is the sole undeniable cause of this infamous rebellion, that it is a war of, by, and for Slavery, is as plain as the noon-day sun,” said members of the 13th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment in February, 1862. Southerners from Morgan’s Confederate Brigade agreed that, “any man who pretends to believe that this is not a war for the emancipation of the blacks...is either a fool or a liar.” Ms. Manning’s research argues that the common Civil War soldier, be he from the North or the South, felt that he was fighting the war over the issue of slavery, that and pretty much none other. This book will appeal to anyone with an interest in the common Civil War soldier. Not his regimental history, or what famous battles he was in, but the soldier for what he was and why he fought.

This book came highly recommended by James McPherson, who uses soldier’s letters and diaries to elaborate on a particular theory or argue a point of view. I’ve read many of his books and when I heard of his recommendation, this became a book I had to read, and I was not disappointed.

Published by Alfred Knopf, April, 2007. Pp 368, $26.95, hard cover, available on Amazon for $17.79.

On the subject of historical fiction and the Civil War, it has been my experience that book lovers generally fall into two categories. Those that read it and those that don’t. There are the purists who only spend time on non-fiction titles, and others who always welcome a well told story, especially on their favorite part of history. Although I read much more non-fiction than fiction, I count myself in the latter category and will always look favorably on any book that draws people into learning about their own history. A work of historical fiction, if done well enough and with an attention to authentic detail, as the best ones are, often sparks further interest and impels people to become engaged in the great tragedy of our nation. One need look no farther than the impact of Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels to validate that argument; historical fiction in the hands of a talented narrative writer can be a special thing.

Now I doubt that a much hyped work of historical fiction being published this Fall, Rhett Butler’s People, will replicate the enormous success of Shaara’s book, but it bears watching. The book, by Donald McCaig, the award-winning author of Jacob’s Ladder, covers the period from 1843 to 1874, nearly two decades more than are chronicled in Gone With the Wind. Twelve years in the writing, and fully authorized by Margaret Mitchell’s estate, it is said to bear favorable comparison to Mitchell’s masterpiece as a masterful story woven by a gifted novelist. Whether that is publisher’s hyperbole, I’ll leave it for readers to decide. Whether it will take a place among the giants of the genre, Red Badge Of Courage, “Freedom”, Andersonville, Killer Angels, and others, or suffer the justly deserved fate of the much panned novel, Scarlett, remains to be seen. Anyway, Publication date is November 6, 2007.

The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech That Nobody Knows

The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech That Nobody Knows It is quite remarkable that what is perhaps the most important speech in American history has received so little careful historical attention. No one can consider Lincoln or the Civil War without referencing the Gettysburg Address, but the story of how it came to be drafted, the setting in which it was presented, and the reactions thereto are so often overlooked. Fortunately, this vacuum has been capably filled by Gabor Boritt in his new volume, The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech That Nobody Knows.

Although the title overreaches, the text itself is very satisfying. It makes good sense that Boritt be the author of this historical examination, as he is one of the foremost scholars of Lincoln and has resided in Gettysburg the better part of three decades. In addition to being the Robert Fluhrer Professor of Civil War Studies at Gettysburg College, he is Director of the Civil War Institute.

The book satisfies in two ways. It is a well-researched and astutely analyzed scholarly text. Yet the account flows well for popular readers, making for that rare combination. The brief speech is intricately tied to an era (the Civil War), a battle, and a place (The Soldiers National Cemetery). Others, notably Gary Wills, have offered philosophical reflections upon Lincoln’s nine sentences. But no one before has so well fixed the words into the context in which they were uttered.

Boritt begins with the aftermath of battle, that “strange and blighted land” overwhelmed with carnage. But he moves quickly to the relief effort where hope faintly became apparent. That hope and meaning for life would appear in full blossom through the expressions of the President come to dedicate the cemetery. Neither the town nor the nation was ready for the moment. Both were utterly overwhelmed by circumstances. Even as the one-day famous words were heard by listeners or read in newspapers, people seemed not to be able to absorb their significance. It took reflection for them and for us to realize that each sentence, each phrase, each word was precisely the right prescription.

The stage is dramatically set as thousands descend upon the crossroads community. Boritt humorously describes the inadequate beds and the reality that many (perhaps even Governor Andrew Curtin) spent the night before wandering the streets in search of a cubbyhole to catch some winks. Some spent the night carousing and it is a wonder that anyone, including the President, would get a decent night’s sleep.

In a series of fascinating appendices, Boritt presents a series of analytical studies comparing the several handwritten copies of the address with the text reported in newspapers. Knowing the precise words may be a bit elusive, but one completes the book with the sense that we know everything we really need to know. It took years for the Gettysburg Address to touch the soul of America and become the iconic expression of the meaning of the war and the mission of the nation. Along the way, the author fleshes out bits and pieces of the ceremony and identities of persons present. Generals Couch, Stahel, Doubleday, Gibbon, and Horatio Wright were part of the ensemble, along with a number of governors. Boritt concludes that Lincoln’s Colored valet not only accompanied him, but may have helped the President in more significant ways than with his clothing. Altogether, the crowd assembled that day “seemed packed like fishes in a barrel,” observed one woman who claimed they all “almost suffocated.”

Though Boritt takes time to describe the editorial comments of Republican and Democratic newspapers, he also carries us into the decades that follow in explaining reactions to the speech. Truly it was a message for the ages, not simply for the moment. The later years would involve the “unfinished work” that Lincoln himself had referenced. Lincoln not only gave his generation a needed gospel (“good news”) amidst the devastation of war, but an inspiration to all of us who have come afterward. Near the end of the book attention is given to a very helpful bibliographical note that demonstrates Boritt’s familiarity not only with the history, but the historiography of the Gettysburg Address. From start to finish, even throughout the endnotes, this is a book to be savored.

Published by Simon & Schuster; November 2006; hardback; 432 pages; $28.00, but discounted at Amazon to $18.48.

Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters

Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private LettersRobert E. Lee. No matter if one is a novice to the study of the Civil War or a jaded, veteran student, Lee is always there, inescapably it would seem, when studying and researching the Civil War. Many books, memoirs, grand treatises, etc. have come down the road of history in the past 144 years about this American icon. Lee has been viewed through so many lenses and angles (militarily, privately, socially, etc.) that a sizeable volume could be written giving interpretations just about the volumes and points of view expressed about the man. Many have tried to truly understand who this man was but it seems that Lee himself is too crafty to let us in completely. He is, in fact, a very complicated individual. Many works, of varying quality, attempt to give us a picture of Lee including Freeman’s four- volume Lee; Emory Thomas’ excellent biography –Robert E. Lee. Other works try too hard in their objectivity and thus become too extreme.

Along comes Elizabeth Pryor. This author does not pretend to have found all the answers to this man that brings to her mind many adjectives (that come to mind after reading his own letters: words such as “witty, bourgeois, self-justifying, scientific, lusty, and disappointed”).

Pryor understands Lee’s image. She set out to find the “man enclosed within that image.” She has read and analyzed numerous letters, many in this work published for the first time, with an eye to capturing more of an understanding of the man himself. What we see in these letters will strengthen what we know and deepen our understanding. The reader will not be disappointed as Pryor takes pains to objectively look at Lee the man – highly intelligent, determined, but with human flaws; seemingly aloof and yet a man passionate about what he believed, cherishing his family, supporting his culture, but above all, his faith and his sense of duty.

Each chapter of the book begins with an actual letter or letters, written mostly by Lee but with other family letters as appropriate. Pryor then uses these letters as guideposts that take us through each phase of Lee’s life in each of the chapters. Of note, the reader will find refreshing two things – Pryor’s objectivity and her avoidance of psychological analysis (psycho-history).

In the first several chapters, we are introduced to Lee’s family. The Lee family became guardian of the Washington legacy. This part of Lee’s life is revealing as the family had traits of blueblood but his immediate family finds times difficult due to an irresponsible father who was also a hero of the Revolution. His mother would provide support and comfort with Lee at a young age taking on an adult role. With a chapter on Lee’s West Point years, we see the man solidify the traits of dedication and uncompromising attention to duty. These would be at odds within the man in his later years as he attempted to balance his duty to his country, state, and loved ones.

Pryor continues through Lee’s life in the remaining chapters that will total Twenty-six in all. So, what do we learn of Lee? We see him deal with the loss of Arlington House, but not before Lee must deal with the inherited slaves. He is awkward and uncomfortable in their managment but acts as antebellum culture would require. He is, to quote Pryor, a moderate when it comes to slavery. Wert recognized this in his work. Lee is philosophically opposed to slavery it appears but pragmatically, takes the line usually encountered in antebellum south writings – that is, in time it should be eliminated. Of course, and as always it seems, Lee and many like him continue on with the status quo of slavery. Lee is a man of his region and time. He displays both compassion and adherence to his cultures norms.

Robert E. Lee disliked not only family disputes, but also avoided disputes between high ranking officers in the Civil War as Pryor points out. He was slow in spotting and promoting talent and slow in removing non-performers. But, he was able to carve out victories, and gave hope to the south and discouraged the northern populace. Pryor’s choice of letters and analysis brings these into greater focus. Still, who lies beneath these accomplishments; accomplishments that ultimately would not be enough for the south to secure their stated goal of independence.

Lee’s spiritual life changed in the late 1840’s; influenced by his wife – a women of strong faith and will but with a frail body racked by arthritic pain. Becoming a Christian and confirmed into the Episcopal Church, Lee’s strong character traits would be strengthened by his faith. Pryor does not give great detail in this regard consequently we learn of nothing new.

That Lee liked “the ladies”, we see in Pryor’s book quite a bit more about how much Lee was, apparently, a genuine flirt. His letters are fascinating to read in this area. But, we find a man who, from all that is known, would not stray and remained devoted to his wife and family – perhaps finding duty and obligation stronger than these temptations. One person in particular, however, a Markie Williams, might lead the reader to believe Lee was not just an ardent admirer. Was Lee in love with her? Pryor does not know or say. Nor will we ever know. Lee showed a lot of affection to many in this regard. Once again, he eludes us.

Lee was very devoted to and loved his wife and seven children. A good father, he could be rather overbearing in his desire to instill all that he desired for them to be. The heart-wrenching death of Anne in 1862 shows us some of Lee’s despair but also, as always with Lee it seems, we are not allowed to see the total depth of his despair and how Lee coped with it.

Throughout the book, Pryor fills the pages with a tremendous amount of information from primary sources as well as discussing and assessing the man and what we can learn from his letters. With an unbiased approach and an intense knowledge of her subject, Pryor gives us a source that every student of the Civil War should avail themselves. This book is not about battles. Here, the serious student will be annoyed by a few errors. In discussing Gettysburg, Pryor, according to the endnotes, has relied on Carhart’s Lost Triumph. After shuddering, the reader will find that, in general, the battle history is reasonably accurate. Also, in relating the early campaign in West Virginia, Union General Rosecrans is misspelled twice on page 320 as “Rosencrans.”

Two traits of Lee struck this writer – his stubbornness (already known) but also his unwillingness to admit mistakes (not so well known). We are all familiar with the famous “it’s all my fault” quote after Pickett’s charge. However, Lee’s stubborn side emerges in a letter to his future wife about setting the wedding date where Lee insisted “But if you do fix it, do not change it. For I am so in the habit of considering an event that I have determined upon a done, & want so readily for its accomplishment, that it is sometimes hard to recall me, & worse, to efface the effects of my commencement.” Stubborn and unwilling to admit a mistake? Pryor covers this area quite well and fills in, in my opinion, a trait not generally known.

After the Civil War, Pryor show a man strong but bitter. The last years tell us of Lee’s greatness and failings as his health and memory reveal a man who spent his life forging ahead, trusting in God that all would work, and toward the very end, a man weary and ready to leave this life. What regrets Lee had come mainly second- hand from others who interviewed him after the war. If these are reasonably accurate, then he certainly held some grudges. But his public personae was always forward looking.

Reading the Man – it is an outstanding work, well researched and a book you will go back to often to pick up details of Lee’s life and family. This writer is still searching, however, to figure out if Lee was inherently as aggressive in war as often thought or was the aggressiveness, while there, pushed forward because of Lee’s very strong sense of duty. The answer lies not in this book but rather is with Lee himself, forever guarded. Nonetheless, Pryor ends her book with this sentence – “Lee beckons us not to attain some impossible height of moral righteousness, but to be fabulous in our fallibility, to face unflinchingly all of the vicissitudes of life, and in so doing to transcend them.” To understand this, one comes away with a better “read” on the man Lee.

Published by Viking, Hardback, May 2007; 688 pages; listed at $29.95 discounted to $19.77 on Amazon.

The Maps of Gettysburg: The Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 – July 13, 1863

The Maps of Gettysburg: The Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 – July 13, 1863Anyone who has ever studied the Battle of Gettysburg can tell you it’s all about the maps. Most histories of the battle include maps, but you have to flip through many pages to find the one you are looking for. Gottfried’s battlefield book is unique, both for the sheer number of maps (140 of them) and for the “easy to find” way they are arranged. Gottfried covers the entire campaign and not just the three days at Gettysburg. Several buffs have remarked they have not seen maps of the Battle of Stephenson’s Depot elsewhere. The large number of maps also allows for a closer understanding of some of the smaller clashes during the fighting. It was a pleasure to see, for instance, maps of the brickyard fighting. Gottfried’s book is advertised as an atlas of the Gettysburg campaign. While it is not the first such atlas, Craig Symonds also wrote one, it is the most complete. (I really miss the color that Symonds used in his maps. Hugh Bicheno in his work Gettysburg also makes good use of color.) The maps themselves compare favorably to those in other battle histories. Homes and farms are clearly marked as are fence lines, water courses, and terrain features. Commanders, regiments and the States they represent are easy to discern. I miss the friendlier scaling and clocks found on the maps of Noah Trudeau’s work, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. I tend to see more of Trudeau’s maps in the hands of battlefield guides than any others. A weakness of the book is found in the visual depiction of Pickett’s charge. The series of maps describing the charge is at a scale that gives the reader a “50,000” foot view of the battlefield. Since most of the important fighting occurred near the angle, several close up maps focusing on the action there would have helped. Trudeau does a better job here, even if you have to have a magnifying glass to read his maps. There is a narrative accompanying each map, but he could have been more succinct and left the telling of the battle to others.

In summary, like Gottfried’s other standard work, The Brigades of Gettysburg, his newest book is an important supplement to any Gettysburg library and belongs on your bookshelf. But I wouldn’t discard the maps you are using from other books, including the work of Trudeau, Harry Pfanz or Jeffrey Hall (The Stand).

Published by Savas Beatie, hardback, June 2007; 384 pages; listed at $39.95 discounted to $26.37 on Amazon.

Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America

Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined AmericaIn the Summer of 1858, Abraham Lincoln was a modestly successful lawyer in Springfield, IL. who had once served a 2 year term in the United States Congress, but who was almost unknown outside Illinois. By the end of 1858, he had a national reputation. How that came about and what it meant for the nation is the subject of this book.

Today, many Americans lament the fact that modern political debates have devolved into rehearsed, rigidly structured, manipulated, scripted, sound bite seeking, televised farces, and suggest bringing back something resembling the Lincoln-Douglas debates in their famous Senatorial contest of 1858. However, as Mr. Guelzo points out, they were not, strictly speaking, debates either. Rather, they were sequential speeches made by each candidate, with the opportunity of rebuttal from each side.

They were, however, unique. First, the mid 19th century was the great age of oratory. “Stump” speakers like Lincoln or Douglas could actually speak in long, complex sentences; argue serious issues in compelling, logical, articulate speech without benefit of notes; and speak, without assistance, incisive, evocative, metaphorical prose. Second, in an age before computers, professional sports, and Reality TV, politics was a grand spectacle. This was a time of vigorous public participation in politics and political discussion. It is almost fantastical to read of ordinary citizens who came by foot, barge, boat, buggy, or train from miles around to stand for more than 3 hours and listen attentively as these two intellectual giants thrust and parried their verbal sabers. It was high drama and grand entertainment compared to the daily grind of life endured by most rural folk, and they loved it. Politics at that time was inseparable from community life and your persuasion was easily discerned by the newspaper you read, for each was rigidly political. Mr. Guelzo does an outstanding job of portraying not only the political but the social and cultural milieu of the time.

One can scarcely imagine two individuals more opposite in appearance and presentation than Lincoln and Douglas. Douglas was 5’4” tall, with a large head, stocky, barrel chested body, and an arrogant, defiant, audacious manner. Lincoln, at 6’4” tall, was lanky and gaunt, and very ungainly in gait and manner. Douglas was sartorially resplendent in a perfectly tailored suit; Lincoln wore a dusty Prince Albert suit with sleeves too short for his long arms. Douglas’s voice was loud, self-confident, and melodious, his enunciation clear and distinct; his gestures eloquent and aristocratic. Lincoln’s voice was high pitched and infused with a distinct Kentucky twang and accent. He often used awkward and absurd looking up and down and side to side movements of his body to add emphasis to his arguments. The effect was dramatic but comical.

Lincoln seemed the very caricature of a country bumpkin, hopelessly outclassed by the aristocratic, polished Douglas, the oratorical champion of the age, and destined for a verbal thumping. But Douglas knew otherwise. He knew that Lincoln was the best stump speaker in the West, and that what Lincoln lacked in majestic bearing and superior elocution, he more than made up for in dogged preparation, trenchant logic, droll humor, and sparkling wit.

They engaged in 7 debates spread August through October, in the cities of Ottawa, Freeport, Jonesboro, Charleston, Galesburg, Quincy, and Alton. Attendance averaged about 15,000 persons. Douglas, who did not have to debate Lincoln but whose risk taking, pugnacious nature did not back away from any political fight, set all the sites and rules and the format never varied. The first speaker spoke for one hour; his opponent for the next 1½ hrs; and then the starter finished up with a half hour. The speaking order was reversed at the next site. They went at each other with biting humor, bitter sarcasms, and hellish fury, and the topic was Slavery and the Union. They never discussed any of the other issues of the day, tariffs, land grants, internal improvements, foreign policy, or the growing needs of farm communities.

At every stop, Douglas delivered virtually the same stump speech as he portrayed Lincoln as a “lying, wooly headed abolitionist” who believed in negro equality; denied that the country can’t exist as half slave–half free; denied blacks were equal, could ever be citizens, or can’t continue to be slaves; flayed Lincoln for resisting the Dred Scott decision of the Supreme Court; and defended the soundness of his “Popular Sovereignty” doctrine. Lincoln, in turn, attacked the Dred Scott decision as settling the stage for slavery to be nationalized; attacked the Popular Sovereignty doctrine; insisted that blacks had “natural” rights to be free, and that that is what the founding fathers intended, as well as to put slavery on a path to extinction.

Lincoln was treading a delicate line here as the farther South in Illinois one went, the more any abolitionist leaning sentiments were despised by pro-slavers and old line Whigs. In town after town, Douglas’s surly race baiting continued as he did his best to speak of equality as though it meant a “black man in every white woman’s bed.”

Lincoln thought slavery was wrong and repeatedly said so in every debate.

After the first debate at Ottawa, which most considered a triumph for Douglas, some questioned the wisdom of Lincoln as a candidate and worried that his “House Divided” speech would prove his undoing. But as the debates wore on, it was Lincoln who got stronger and Douglas who faltered. Toward the very end, Douglas’s health weakened and he was said to be drinking heavily. For those who thought that the foremost debater in the land would crush Lincoln, it was shocking. Lincoln not only gave as good as he got, but he was whipping Douglas with the force of his moral arguments. As Guelzo observes, “at the deepest level, what Lincoln was defending was the possibility that there could be a moral code to a democracy.”

Time and again, Lincoln deflected Douglas’s bombast and race baiting with humor, logic, and reason. Further, it is Lincoln’s unforgettable phrases, splendid metaphors, and prophetic appeals that linger in the mind. And Lincoln was the winner in another sense. The debates were published into a book that cleaned up his syntax, silenced his twang, and removed his awkward gestures and gawky appearance from public view. In the election for the Senatorial seat for which they were running, Douglas did win that November. But that didn’t really matter. Lincoln was a man with a future.

Readers are helped along by the authors’ creative use of grids to clarify each debate, and his engaging narrative of each puts them in a clear focus.

Certainly, Mr. Guelzo has added another award winner to his pedigree as one of the foremost Lincoln scholars of our time. It is a fascinating story, brilliantly told, and a valuable addition to the Lincoln canon.

Published by Simon & Schuster, Hardback, February 2008; 314 pages; listed at $26.00 discounted to $17.16 on Amazon.

During the Civil War, numerous daily, weekly, and monthly newspapers and magazines appeared – providing a means in which to satisfy the public’s thirst for information about the war and its progress. The media the public turned to for news and opinions were themselves as opinionated as their readers. In many cases, the periodical added fuel to a fire already out of control or reigniting a population’s waning desire to continue the war effort. Following the war, veteran’s groups and associations began to produce a mountain of literature about their experiences. Over time, these grew into GAR publications, the Confederate Veteran Magazine, the Southern Historical Society Papers, as well as numerous articles that would eventually be collected together – e.g. the Century Magazine, later compiled into the well known Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

With that genesis, the modern reader is not without many periodical sources as well. Of the better known, they include Civil War Times Illustrated, America’s Civil War, Blue and Gray, North and South, The Civil War News and The Courier. Also, for the relic collector, there is North and South Trader. There are several others that are narrower in scope – The Watchdog, a publication that assists reenactors in determining the authenticity level of reproduction uniforms and equipment; The Artilleryman —for artillery reenactors, and The Camp Chase Gazette—also for reenactors. These last several have some good points when the research is of a high level but that does vary some. Of course, there is Gettysburg Magazine with numerous articles.

Avid students of the war, who take scholarship seriously, have made several publications their top choices. For this writer, they are Blue and Gray, North and South, The Civil War News, and Gettysburg Magazine. However, Civil War Times Illustrated cannot be overlooked in the 20th century history of Civil War periodicals. It is the granddaddy of them all. The first issue rolled off the press in April of 1959 as Civil War Times and changed to its current name in 1963. Over the years, this magazine was one of very few the Civil War student could look forward to reading. After other publications appeared, competition followed. No longer the only kid on the block, it seemed the magazine began to struggle. Into the 1990s, the quality of the articles, in general, did not seem to be on a par with Blue and Gray magazine. In 1998 I left this old friend behind, finding more satisfaction in two others.

For the war in general, Blue and Gray and North and South provide the reader with various articles and topics of great interest to all students of the war. Blue and Gray, in general, is what one might call a more concentrated strategic and tactical level publication. The authors know their stuff and the maps are terrific along with the “general’s driving tour.” Some articles receive a lot of mail, pro and con, and this helps the student sort out the issues. Each, of course, must make up their own mind. I always look forward to receiving Blue and Gray.

North and South magazine covers, in addition to military topics, a good variety of the social and political aspects of the war. The magazine offers scholarly articles with a variety of views. Often the reader is treated to articles that go back and forth on generals or other subjects where a number of well known historians render their opinions. These are worthwhile debates – try it, you’ll like it.

The Civil War News is a monthly newspaper that covers a variety of topics of what is currently going on in the Civil War Community. It is usually very up-to-date in its material and has something for most everyone. It is never disappointing.

Of course, for the Gettysburg savant, there is Gettysburg Magazine. Published twice per year since 1989, its founder, the late Bob Younger of Morningside books, has treated us to high quality articles over the years. As with anything, it would appear that time is taking a bit of a toll as each issue gives one the feeling that a few articles are too much re-hash. Still, it remains a winner. How long into the future it will continue is a question not yet answered.

While each has something to recommend it, this writer believes Blue and Gray, North and South, The Civil War News, and Gettysburg Magazine are the best of the lot and worth a subscription.

This Republic Of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War

This Republic Of Suffering: Death and the American Civil WarHarvard President Drew Gilpin Faust’s book, This Republic Of Suffering, attempts to explain how a shattered nation dealt with death and the Civil War. Faust’s academic work analyzes how the horrific amount of war death affected both the individuals involved and the noncombatant citizenry of the time. With so much death and sorrow, how did the nation come to grips with so much pain and suffering?

First, one must understand the pre-war ideals of a “good death.” Family members usually died at home surrounded by their loved ones. After the death, there was a body to view and to bury. Most important, there was a grave to visit and to mourn at. The Civil War, for the most part, changed the ritual of mourning. Loved ones were being killed and buried in mass graves far away from home.

Faust detail the letters of dying soldiers, their comrades post-mortem letters sent to comfort families with tales of bravery and the love of God and country. Faust covers everything from identifying bodies to the establishment of national cemeteries.

General Robert E. Lee emotionally summed it up after the death of General A. P. Hill, “He is at rest now, and we who are left are the ones to suffer.” Death and suffering landed on every doorstep. Faust’s insightful and well researched book focuses on the emotional, psychological, cultural and spiritual impacts of the war. This Republic Of Suffering is recommended to those interested in both the Civil War and mid-nineteenth century culture in America.

Published by Alfred Knopf, hardback, January 2008; 368 pages; listed at $27.95 discounted to $18.45 on Amazon

Gettysburg Heroes: Perfect Soldiers, Hallowed Ground

Gettysburg Heroes: Perfect Soldiers, Hallowed GroundOne of my favorite books on the battle of Gettysburg is the classic: Twilight on Little Roundtop by Glenn LaFantasie. I enjoyed that book so much that I eagerly awaited his latest work: Gettysburg Heroes: Perfect Soldiers, Hallowed Ground.

I won’t say I am disappointed, but this latest work does not have the breathless excitement that his previous book had.

Instead, LaFantasie examines the lives and experiences of several key personalities who gained fame during the war and after. The battle of Gettysburg is the thread that ties these Civil War lives together. Gettysburg was a personal turning point, though each person was affected differently. Largely biographical in its approach, the book captures the human drama of the war and shows how this group of individuals—including Abraham Lincoln, James Longstreet, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, William C. Oates, and others—endured or succumbed to the war and, willingly or unwillingly, influenced its outcome. At the same time, it shows how the war shaped the lives of these individuals, putting them through ordeals they never dreamed they would face or survive.

I can’t get it out of my mind that some of the material in this book is leftover from previous works. For example, William Oates from Alabama gets the most ink (although his name is hardly the one name that comes to mind when one thinks of “Gettysburg Heroes”.) It is not a coincidence that another of the author’s works is: Gettysburg Requiem: The life and lost causes of William C. Oates. Joshua Chamberlain of LRT fame also gets good play, but again the inclusion of Chamberlain would seem to be a continuation of earlier efforts. Still, this latest book is good reading, and can we ever have too many books on Gettysburg? While I may not buy this one for myself, I might give it to a friend who is getting interested in the people who make up the story we know as “Gettysburg”

Published by Indiana University Press, hardback, March 2008; 279 pages; listed at $24.95 discounted to $18.96 on Amazon.

Lincoln’s Rise to the Presidency

Lincoln’s Rise to the PresidencyThe year 2009 will mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln. We can expect to see new books detailing Lincoln’s life and presidency and seminars devoted to Lincoln. Indeed, the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College had its 2008 program devoted to Lincoln’s presidency, and the upcoming 2009 CWI will focus on Lincoln’s assassination and on Mary Todd Lincoln.

One new book, looking at Lincoln is “Lincoln’s Rise to the Presidency” by William C Harris. This book examines Lincoln’s life and his character and his becoming a prominent member in the Illinois anti-slavery movement. Harris shows that Lincoln was really a political conservative, devoted to the principles of the US Constitution. Repeatedly in the book, Harris shows how Lincoln framed his arguments in view of the intentions of the Founding fathers.

One aspect of the book I enjoyed was how Harris challenges any revisionist interpretations of Lincoln’s life. Indeed Harris will openly mention different authors who have written about Lincoln and will challenge them on their interpretation of Lincoln’s life and motives. He then allows the reader to make his or her own decision.

I purchased this book after hearing Mr. Harris speak at the CWI this past June. Numerous authors had spoken and their books were available to be bought. I think I made the correct choice as I could not put this book down at all, and read it in practically one sitting. If you are interested in Lincoln’s becoming President, this book would be a valuable addition to your library.

Published by University Press of Kansas, hardcover, April 2007; 412 pages; listed at $34.95; discounted to $23.07 on Amazon.com.

Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President’s War Powers

Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President’s War PowersFate dictated that Roger B. Taney, a strict constitutionalist and states rights proponent would be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court just when Abraham Lincoln ascended to the presidency and the union was disintegrating. Lincoln’s use of power to hold it together ran straight up against Taney’s vehement opposition, thus setting the stage for a monumental conflict that is the subject of this outstanding book by James Simon.

Taney, little remembered today except for his infamous Dred Scott decision, was a Marylander who had freed his own slaves but remained a bitter foe of abolitionists. He drew a sharp distinction between slavery on moral grounds and slavery on constitutional grounds. He believed blacks were excluded from the constitution as citizens; that they were inferior beings, merely property under the constitution, and that the federal government could not prohibit their being taken into the western territories. Nor could the government prevent newly constituted territories or any states from prohibiting slavery within their borders. Using the Dred Scott decision as his platform --- backed by four other Southern justices who sided with him ---Taney declared the illegality of the Missouri Compromise, saying that blacks could not be United States citizens and had no rights that whites were bound to respect. Mr. Simon clearly defines Taney and the political context against which Lincoln rose to power with views directly opposite those of Taney, but for a singular exception: Lincoln too believed that, constitutionally, a President had no power to abolish slavery in those states where it currently existed. However, Lincoln held fast to the view Congress did have authority to limit the spread of slavery and the “intent” of the founding fathers to do so, or why else did they adapt the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, prohibiting slavery in the northwest territories; and put into the Constitution the ending of slave importation, effective in 1808.

Simon vividly depicts what happened next when Lincoln ascended to the presidency.

First, he said in his inaugural address that Southern states have no constitutional right to secede from the Union. A crisis soon surfaced in nearby Maryland. There were problems getting the early volunteers through Baltimore to come to the defense of Washington. Southern Maryland and the eastern shore were pro- south and pro-slavery, and secessionist sentiment abounded in the Maryland legislature and judiciary. Congress was in recess and the union was busting up. Maryland was leaning toward secession; something Lincoln cannot allow. He takes the radical action of suspending the writ of Habeas Corpus and the battle with Taney is enjoined. Lincoln has various Maryland officials imprisoned under a charge of aiding secessionists, saying he has the authority to do so because the writ can be suspended during a “rebellion or invasion” of the United States to safeguard the public.

This dispute is effectively rendered by Simon without bogging the reader down in legalese. Over the remainder of the book, Simon relates in a clear, engaging narrative all the clashes between Taney and Lincoln. Specifically, that the following Lincoln moves were all unconstitutional: preventing southern states from seceding; blockading Southern ports; seizing cargos from vessels going to or leaving Southern ports; the Legal Tender Act; and the Government’s military draft statute. Given the opportunity, there is little doubt Taney would have declared the unconstitutionality of the Emancipation Proclamation too. It seemed everything about wartime Washington infuriated Taney, and no individual infuriated him more than Lincoln. In particular, the latter’s “tyrannical usurpation of power.” Chief Justice Taney became Lincoln’s “unwitting foil”, challenging Lincoln’s sweeping executive powers at every opportunity, officially and unofficially. Undeterred, Lincoln fought, dismissed, or ignored Taney’s opinions and rulings. Simon emphasizes that “Lincoln was not to be denied, by Taney or anyone else, in his goal to preserve the Union” and “to free African-Americans from slavery.” Lincoln, as he famously said, did not think “that the framers intended for the President to sit idly by (with Congress adjourned) and allow the nation to be torn to pieces by a rebellion.” As for his protagonist, Taney, the author gives us an understanding of his brilliant gifts of analysis and mastery of legal detail that stand as a counterpoint to his Dred Scott decision. It’s a fascinating story, told in a compact, 288 pages that never flags, and I give it an enthusiastic two thumbs up!

Published by Simon & Schuster; paperback, November 2007; 286 pages; listed at $15.00; discounted to $10.20 on Amazon.

Imboden’s Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign

Imboden’s Brigade in the Gettysburg CampaignFor all the attention given to the Gettysburg Campaign, little can be found in one source about Imboden’s Northwestern Virginia Brigade. Steve French gives us a “one stop” view of Imboden’s movements and actions from June 9th through July 24th. Included in French’s work are a number of interesting photos/views of Cumberland, Md., McConnellsburg, Mercersburg, Greencastle, Cunningham’s Crossing, and others. These views enhance a strong narrative on Imboden’s mission that includes their actions and activities along with those of McNeil’s Partisan Rangers (“Land Pirates”) and their effect on the civilian population in towns and farms on Lee’s left flank.

Imboden’s orders are to protect Lee’s left (including the destruction of bridges), and gather supplies. French gives us a good picture of the enormity of Imboden’s task. With two regiments and a six gun battery, Imboden will skillfully go about his duty. The reader is introduced to war’s effect on civilians in an up-close and personal way. The reader will begin to understand that Imboden and his men were not out for a joy ride prior to Lee’s retreat on July 4th. His subsequent problems at Cunningham’s Crossroads and Williamsport defense are certainly well chronicled in other places, but French, by taking us from June 9th, leaves you with a better understanding of the depth and difficulty experienced by Imboden’s command. We also learn of Imboden’s ability to use a “rough” force and handle them as well as he did.

French moves us out of Western Virginia toward the Potomac with numerous accounts of small actions along the way. Moving into Maryland and Southern Pennsylvania, we learn of divided loyalties in many area and places - making it a challenge to know friend from foe without trusted locals to know the difference.

French chronicles very well the civilian responses and views. A strong point of this book is the use of many primary sources. Numerous vignettes keep the story moving. War up-close – consequences, bad or good, erupt to keep the reader wondering what other event may come from an unlikely quarter.

Also, we find Lee himself is a strong supporter of Imboden. One gets the sense, though, that Lee (Imboden and his command, by the way, reported directly to Lee) was comfortable in the role played by this command. The reader gets the sense that Lee was expecting only what he wanted them to do and was not about to give them an assignment that Lee felt was beyond their capabilities. This brigade had a reputation of being better at plunder, given their genesis, that French explains and details.

The appendixes are interesting—especially the appendix on damage claims that shows not only what was lost by the civilians but what piqued the interest of the Confederates.

The reader will find a couple of things wanting. Although not many grammatical or typo mistakes, there is not an index in the back, nor a listing of maps and illustrations in the front. The several maps are OK, but a few more, and easier to see maps, would have been helpful as well as more details of movements in some of the skirmishes. It seems, of late, to this writer, that including maps with detail are too often shunned and that is a shame. Still, we have some here that is a good start. A revised edition could include more detailed and clearer maps- taking this work from a strongly recommended book to approaching a “must have.”

The endnotes are extensive but the author calls them “footnotes” even though they are at the end of the book. The endnotes are properly after the appendixes but improperly before the bibliography.

It still mystifies me that in discussing McClanahan, authors seem to think they know exactly what type of guns he has. I believe French is following Brown’s book on Lee’s retreat and Brown does not give his source (there is none as far as this writer knows). The Gettysburg savant will catch a couple of errors of fact but they are minor.

That said, at $19.95, this is a strongly recommended work that fulfills its title in the broader picture and story of Imboden and his command in the Pennsylvania Campaign.

Published by Morgan Messenger, 2008. Pp. 257, $19.95, soft cover, photos, maps, illustrations, notes, appendix.

In the introduction, author Philip Laino describes himself as more of a compiler than a historian, cartographer or even an author. Regardless, Laino has “compiled” four hundred twenty-one maps, impressive and comprehensive maps, that take the reader through the the Gettysburg Campaign from June 3, 1863 thru July 14, 1863 and that will please the Civil War community and in particular the Gettysburg buff, serious student of the war, or even the Gettysburg savant. Included with each map is a text that explains, clarifies, and compliments each map. Of note, Laino includes some “Alternate Maps” for those facets of the battle in dispute leaving to the reader to decide which version they believe is more valid.

Also, in the Introduction, Laino points out that “facts” are slippery and elusive and subject to interpretation (welcome to history). Nevertheless, Laino has presented an outstanding array of maps, spiral bound for ease of use, that the reader will return to again and again. Included at the end of each section are footnotes that give much information on sources for further reading as well as supplemental information to the maps. The footnotes alone are quite extensive and are a ready source for further reading. His notes also enumerate various points of view in a number of areas as well as noting how different maps used in his research contradict each other.

As a bonus, he lists in the back Union and Confederate units sorted by state with strengths and percentage of losses. A most useful tool. In addition is an Order of Battle. All strengths and losses from both are from Busey and Martin (Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, 2004 edition).

This writer noticed very few “errors” of fact. Serious students of the battle may or may not agree with every little detail on every map but as far as I have found, not yet having a chance to review each of the 421 maps in complete detail, nothing appeared to be glaringly incorrect.

Laino’s use of alternate maps is most refreshing. In particular, alternate maps, four of them in fact, are provided for Vincent’s approach to Little Round Top. In addition, the south cavalry field fight on July 3rd has an alternate map although here this writer would like to have seen Andie Custer’s version but Laino does reference that as an alternative.

A salient point of this collection of maps is the campaign movements and actions prior to and after the three days of battle.

Occasionally, while attempting to keep the text “barebones” on each map, some statements could give a false impression. On page 141, Laino states Sickles has moved without orders from Emmitsburg. Sickles has orders but they conflict. In one sense it is truce but lacks explanation. This could confuse the beginner who does not have a good background of knowledge on the campaign.

Laino also cautions that these maps are approximations and not intended to hold up to scrutiny with calipers to measure regimental or brigade fronts, or calculate distances between landmarks. With as much detail as there is on these maps, they will not be perfect or the last word. That will most likely never occur.

The atlas is very well organized. Divided into sections for the campaign prior, each of the three days, and the campaign after, the reader can easily find what they want. The top of each page is numbered with a title for what is happening one that particular map. On page 97, map 1-20 (the 20th map on the first day) is titled - Pender Mover Up. Robinson and Rowley Deploy. Each day begins with an overview or situation map that is also included at other times during each day’s battle. In some cases, such as the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard, two maps are included on one page to give more detail of complicated movements.

An index and bibliography round out a most impressive work that is priced at $40.00; less than 10 cents per map. The Gettysburg Campaign Atlas is highly recommended and deserves a place in every serious student’s library. You will return to it many times as a great reference source on several levels.

Published by (Ohio: Gettysburg Magazine, 2009. Pp. 481, $40.00, soft cover, spiral bound, maps, notes, tables, bibliography, index. ISBN 978-1-934900-45-1).